Since its introduction more than 50 years ago, ketamine has proven itself to be a safe and useful agent for use as anesthesia, and—more recently, and at lower doses—as an effective psychiatric drug. At sub-anesthetic doses (sufficient to achieve a therapeutic effect but not enough to anesthetize a patient), ketamine has been increasingly used to treat depression, with good results, particularly in cases where other treatments have failed. Its rapid onset makes it an especially effective tool for treatment-resistant major depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. Now, emerging evidence provides hope that it may also be effective in improving function in patients with cognitive deficits.

Neurological disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, epilepsy, and traumatic brain injury are frequently accompanied by cognitive deficits that profoundly affect a patient’s daily functioning and quality of life. Existing treatment strategies for these impairments, such as cognitive remediation therapy, support patients as they engage in cognitive tasks, promoting the neuroplastic process in which the brain reorganizes itself. Still, these strategies are mostly intended to compensate for lost ability. What if we could actually restore some of those lost functions, rather than just compensate for their loss? What if there were a supplemental medicine to facilitate neuroplasticity? Some studies suggest that ketamine could help.

Many neurological disorders are accompanied by depression, which can compound the effect of the disorder on cognitive function. Research suggests that ketamine used for depression in psychiatric patients has cognitive benefits in that population (Yingliang et al, 2025). Sub-anaesthetic doses of ketamine have been shown to improve visual memory and working memory in individuals with treatment-resistant depression, suggesting that the resulting improvement in cognition may be of help in reducing depressive symptoms. (Marcontoni et al. 2020; Yavi et al. 2022). Other studies have shown that ketamine can improve information processing speed, attention, working memory, and flexibility. (Hayes et al, 2012). This dual-action potential of ketamine provides a rationale for investigating its application in neurological rehabilitation.

Ketamine and Neuroplasticity

The key may be in ketamine’s potential to induce neuroplastic changes in the brain. Researchers are looking for ways to tap that potential, to harness the brain’s ability to change and rewire itself, to restore cognitive function in those who have lost it to disease or injury. Since depressive symptoms can exacerbate deficits in information processing, attention, working memory, and executive function, a medication that provides both an antidepressant as well as neuroplastic effect may exert positive influence on neurocognitive outcomes.

The research into ketamine’s effect on cognitive function is in its earliest stages, with few human studies so far. In animal models, though, ketamine promotes both synaptogenesis (the formation of new synapses) and neuroplasticity (the brain’s reorganizing itself) in the medial prefrontal cortex and some limbic regions. It activates the transmission of the neurotransmitter glutamate in the prefrontal cortex, an area of the brain associated with cognitive flexibility and problem solving. That glutamate transmission not only has an antidepressant effect, it also enhances function in that area of the brain. Low doses of ketamine also modulate inflammation in the brain.

In animal models, ketamine has been shown to activate many of the signals implicated in neuroplasticity. We can see the effects of the drug in brain imaging, which has shown enhanced connectivity following the administration of low doses of ketamine (Abdallah et al 2017). If it turns out that ketamine induces a window of neuroplasticity that makes the brain more receptive to neurorehabilitation, low doses of it could be a beneficial component of cognitive remediation treatment.

Positive Effects of Ketamine on Cognition

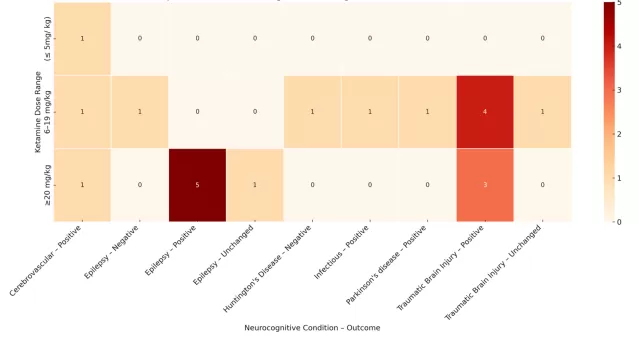

Along with my colleagues Guido Mascialino, Ph.D., and Jose Eduardo Leon Rojas, M.D., of Escuela de Psicología y Educación at the Universidad de Las Américas in Quito, Ecuador, I recently conducted a review of the literature on the effect of ketamine on cognitive function. We looked at multiple studies of ketamine and its derivatives (r-ketamine, s-ketamine, and racemic ketamine) that had explored their cognitive effects on neurocognitive impairment, cognitive dysfunction, and neurocognitive disease. One human study inc

luded 10 patients diagnosed with Huntington’s disease; the animal research was conducted on 366 rodents in 21 different studies. In the animal tests, our team identified an overall positive neurocognitive effect in 93.2% of brain-injured subjects. Memory and spatial learning were the most affected domains. The human study did not show a benefit. Further research will be needed to explore differences in animal and human studies.

In the field of neurocognitive rehabilitation, where the effectiveness of treatment can be limited by progressive neurodegeneration, impaired self-awareness, depression, or complex comorbidities, the potential emergence of a drug capable of enhancing cognitive functioning is both scientifically compelling and clinically hopeful. Numerous studies have shown encouraging results regarding safety, efficacy, and longevity utilizing sub-anesthetic doses of ketamine in mitigating psychiatric symptoms (Ragnhildstveit et al 2023).

By integrating pharmacological agents like ketamine with behavioral and cognitive remediation strategies, we open the door to novel, interdisciplinary approaches to the treatment of organic neurological disorders, rooted not only in symptom mitigation but potentially in cognitive restoration.

There remains a significant paucity of research directly investigating ketamine’s effects within adult neurological populations, but the findings in animal models underscore the need for further exploring subanesthetic ketamine as a cognitive adjunct in neurorehabilitation for patients with organic neurological disorders and traumatic brain injuries.

A complete report of our team’s studies is now being prepared for publication in an academic journal.